In 2022, I wrote revised lyrics for Peter Sarstedt's 1969 song, 'Where do you go to (my lovely)'.

You can read my lyrics below...

And/or listen to my audio version here: Where do you go to (2022)

You

talk like a Russian princess

With plumped lips

& a ripe cupid’s bow

You blow a perfect air kiss

To those

that you don’t really know,

no no, not

at all

You

dance like they do on Tiktok

Swinging

shoulders & hips to the beat

You know that you

look very hot

Arousing envy in

all whom you meet, what a feat, feel the heat

[CHORUS 1]

But

where do you go to my lovely

when your

mobile phone battery is dead

tell

me the thoughts that surround you

I

want to look inside your head,

yes I do

Your

clothes are all

made to highlight

your features

your curves and your hair

Your bodycon

fashions fit tight

Cos you are an

influencer, so pretty, we can see

Your breasts are

so perfectly formed

That they dare us

not to stare

We wonder if

they’re silicone

Or maybe a gummy

bear, something’s there, you never share

[CHORUS 2]

Where do you go to my beauty

when you’re not

swiping left or right

Tell em the thoughts that surround you

When you're alone in your bed in the

night, out of sight, whatta fright

You're seen in all the right places

Snapchat, Insta,

Youtube and the net

Posting

perfectly-posed smiling faces

Seeking likes

from those you’ve never met, never could, never should

We've seen all the meals that you've eaten

All the places

that you’ve been

We've seen all the people

you’re meeting

Even seen your

daily routine, how serene, oh so keen

[CHORUS 1]

But

where do you go to my lovely

when your

mobile phone battery is dead

tell

me the thoughts that surround you

I

want to look inside your head, yes I do

You proudly

promote your webpage

Adding daily to

the image you’ve spun

Yeah, it’s a

fake for the glittering stage

And you keep it just for fun, for a laugh, a-ha-ha-ha

They say with the

support of your followers

You’ll soon be a millionaire

But what if it

makes your life hollower?

Do

you wonder if they'll really care, or give a damn

[CHORUS 2]

Where do you go to my beauty

when you’re not

swiping left or right

Tell me the thoughts that surround you

When you're alone in your bed in the

night, out of sight, whatta fright

[CHORUS 1]

But

where do you go to my lovely

when your

mobile phone battery is dead

tell

me the thoughts that surround you

I

want to look inside your head, yes I do

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

For more information about Peter Sarstedt's original version of this song: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Where_Do_You_Go_To_My_Lovely

Words from Sarstedt's original version included in my revised version are highlighted in pink.

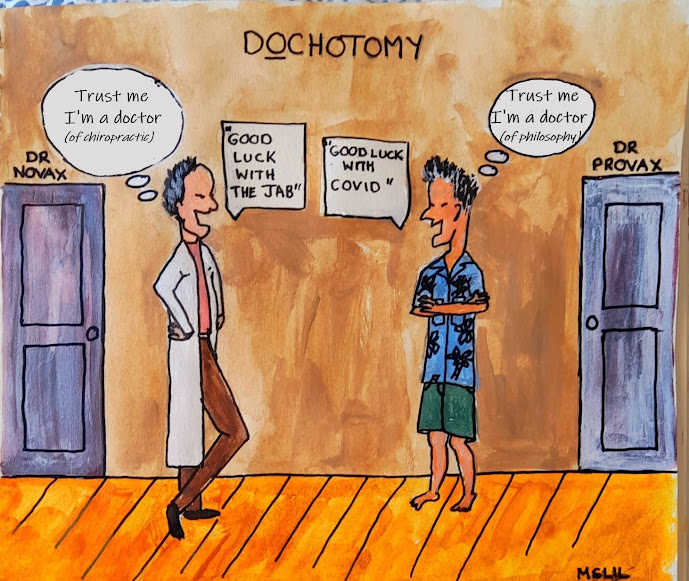

The supporting image for this post was generated by DeepAI Image Generator prompted by "Russian social media influencer, plumped lips, bodycon dress, taking a selfie"!